Guest post authored by Nate Martins from HVMN.com

What is speed? If we’re opening the dictionary, it’s a measurement of the rate at which someone or something is able to move; it also means to move quickly. Speed is both relative and concrete. It’s both an exact measure and a feeling with wholly different meanings depending on the context.

Speed is inexorably linked to time: seconds, minutes, mile splits, PRs. It can be easy to forget the idea of being fast, the heavy breathing, wind-through-your-hair, quad-burning sensation in which runners know they are hitting the ground but feel as if they’re floating.

Sam Robinson is a writer and marathoner–he has a PhD in history, has been featured in Outside Magazine, and is a fixture in the Bay Area running community. He recently discussed the idea of running philosophy on the HVMN Podcast.

“Fast is relative. It’s always good to keep that in mind.” — Sam Robinson

Fast is a feeling, one that maybe can’t be associated with time for all athletes.

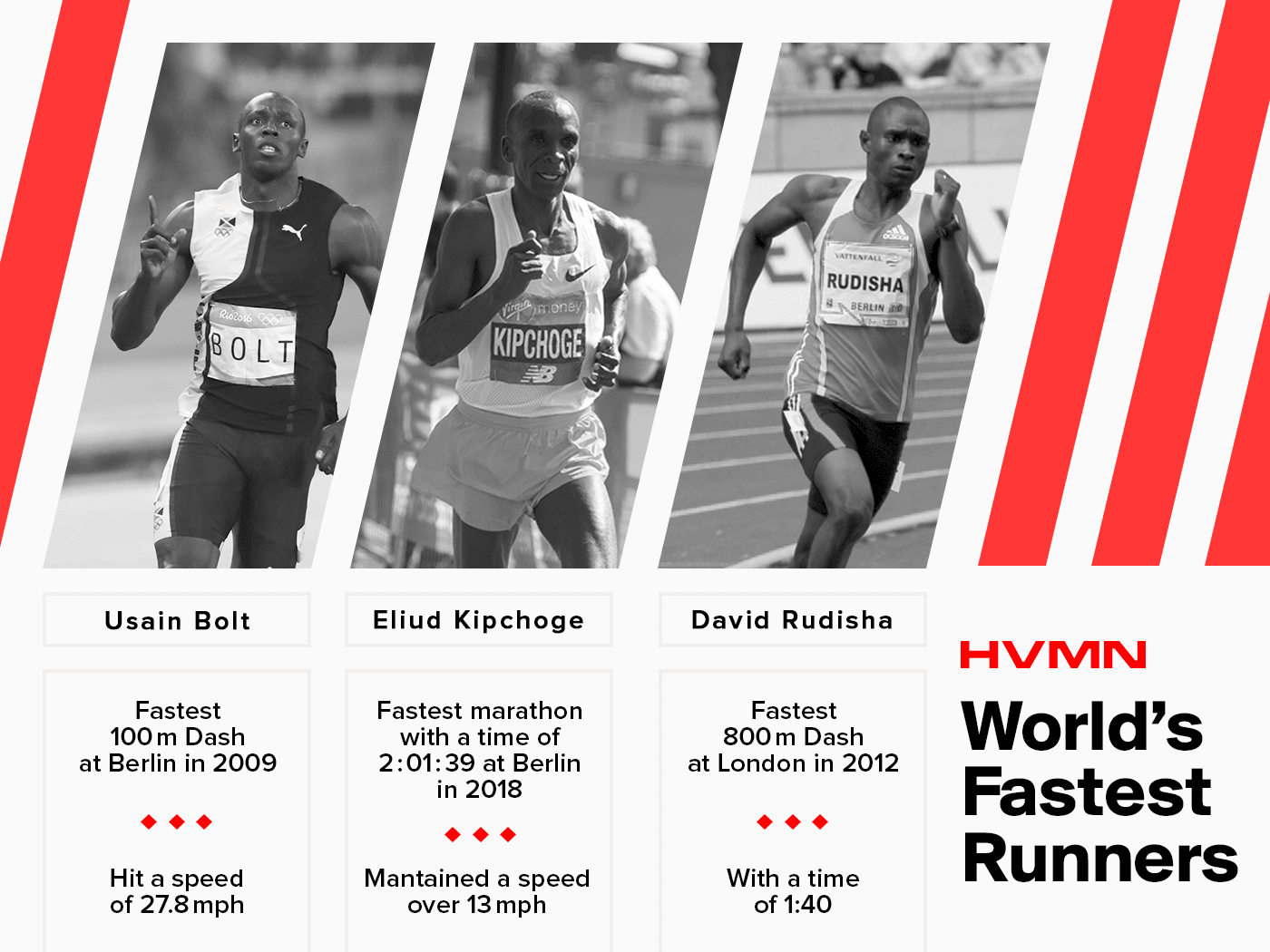

Keeping Pace with the World’s Fastest Runners

During the 100m dash at the 2009 Berlin World Championships, sprinter Usain Bolt hit 27.8mph. Marathoner Dennis Kimetto ran the 2014 Berlin Marathon in 2:02:57 which was the fastest marathon of all time–until Eliud Kipchoge smashed that record on September 16, 2018 (also at Berlin) with a time of 2:01:39.

These runners exhibit different kinds of speed, each fast in their relative events. While Bolt hit a top speed of nearly 28mph, Kipchoge maintained over 13mph during his world-record setting marathon. The result was an average mile time of 4:38, faster than the max speed of the average treadmill (5 minutes per pace). These are the two extremes: sprints and marathons are almost entirely different sports and ways to exhibit speed.

Between these two efforts, middle distance running (800m, most commonly) provides a unique physiological middle ground.

One study cites the contribution from aerobic and anaerobic variables as allowing a runner to maintain speed during middle distance races. These runners are able to produce velocity without impairment from things like VO2 max (long-distance running), and lactate threshold (sprints).1

The world’s fastest 800m runner is David Rudisha, who holds the world and Olympic record set at London in 2012 with a time of 1:40. That effort broke his own record, set in 2010. Before that? The record was set in 1997 by Wilson Kipketer (who broke his own record several times). And before that? The record was set by Sebastian Coe in 1981. This is interesting when compared to marathon records (broken every few years) and 100m world records (broken even more frequently).

This is all to say that fast doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It depends on things like distance, event, output, and maybe most importantly for the casual runner, personal goal: a number, denoted in time, less than your previous run.

We are not Bolt or Kipchoge. But we share a desire to run faster, whatever that may mean to you as a runner.

Mental Techniques

Running faster is something that must be achieved through physical ability–the body is what propels us forward. But now more than ever, the mental aspect of endurance exercise is being considered a powerful tool to push the body to extreme lengths.

“We’re so fixated on screens. Running is one of the times I can get away from that and be in my own head.” — Sam Robinson

The body and mind are linked; while we’ll explore physical aspects of technique and pacing, we’ll also address mental strategies to employ while on the road or the course.

Welcome the Pain

We previously discussed motivational techniques for runners, which points to embracing pain as a way runners can push themselves to log miles every day. The same is true for running faster. There’s an element of discomfort that must be welcomed in order to increase pace.

“Try not to see it as pain, just an intense sensation like spicy food or dark chocolate.” — Michael Brandt, HVMN Co-founder and COO

This is especially difficult for runners who are just starting because they’re not used to the feeling of pain. During workouts like speed training, the pain will come–it’s about being ready for it, anticipating it, and eventually, embracing it.

The pain will lessen with training. Crossing the lactate threshold is the point at which the body cannot recycle the lactic acid accumulated in the blood–it’s then that the body begins sending pain and nausea signals in an effort to make you slow down and thus recycle all that lactic acid. But you can train to increase that lactic threshold and decrease the pain.

With training also comes a knowledge of your body and an understanding of pain, remembering how it feels and at what point in the run it’ll hit.

Positive Thinking

The power of the mind can’t be understated–being aware of your thinking, and how those thoughts make you feel, can have a positive or negative impact on performance outputs. Sometimes telling yourself “you’re great” is the first step to actually making that happen.

One meta-analysis concluded the strategy of self-talk facilitates learning (so it can also help training) and enhance performance.2 Since self-talk has an impact on performance, it’s important to make that self-talk positive.

Cindra Kamphoff has a Ph.D in performance psychology, and she is a performance coach to professional athletes, executives and championships teams from all over the US. She understands the power of the mind and helps athletes harness it. When speaking about the mental aspect of sport, she had this to say: “The negativity is going to come, the disempowering thoughts are going to come because you’re pushing your body. You don’t have to believe them.”

While talking to yourself during a run, it also helps to be mindful. Many runners reach a flowstate of zen or a meditation-like experience. This happens during the run, but its power can be harnessed while off the trail. One study showed that several weeks of mindfulness training could help elite athletes adapt better to stressful situations.3

The ability to harness the connection between body and mind may lead to better results.

Chunking

No, this isn’t adding carbs to your pre-workout.

Breaking a casual run or race into chunks can help–especially for longer runs. This technique can help by making the total mileage feel less daunting. For a marathon distance, a popular way to break it down is into two 10-mile runs and a 10k.

Even on a smaller scale, chunking can be similar to gamifying the run. If you’re running in a city, you might push yourself to the end of the block. During a race, it’s undeniable that seeing the finish line can allow you to tap into a new running gear and push to the end.

Breaking down a run into smaller sections may help increase speed incrementally, which will likely lead to a better overall time.

Training Smart

Training is like juggling. Breathing, form, power–all these things are on your mind with each stride. When one is dropped, the others tend to follow. But it’s during this training process that the best habits are built. And remember, it’s a process.

“Running is about playing the long game. Think of it like a house. A good race or bad race is a single brick in the edifice of your long-term fitness.” — Sam Robinson

Things like intervals and tempo runs can help. It’s also important to track your progress: keep a training log to see how you’ve been able to increase speed after all that hard training.

Intervals

Intervals are great speed workouts for both the aerobic and anaerobic system. They consist of short, high-intensity bursts followed by slow recovery phases which are repeated one after the other. One of the earliest forms of interval training was the Fartlek method (Swedish for “speed play”), and today, many athletes use high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Sometimes, running fast means actually running fast.

Generally, these workouts are ten seconds to several minutes long, run nearly at maximum effort, followed by a rest period of up to four times the length of the effort itself. The shorter the interval, the more of them you’ll likely do.

But the length of intervals (time and distance), power of those intervals, and the rest period, should be optimized for the specific runner. Elite runners can do four intervals of ten minute runs at their 5k pace. Most runners won’t be able to maintain that. An average interval workout is an 8x4: eight repeats of a 400m run done in 90 seconds with a two-minute recovery.

One study in soccer players found that HIIT improved maximal aerobic speed.4 And recreational runners can improve their running economy by replacing aspects of their conventional training with long-interval running.5

Hills

Hill training usually targets power in the legs, meaning higher output. One study found that six weeks of hill workouts increased top speed for runners, while also allowing them to sustain that speed 32% longer.6

Hill repeats are similar to interval training in that they’re usually conducted in short bursts. First, warm up. Then find a hill that’s about 100m long and run hard to the top, with the jog downhill serving as the recovery period. Start with two or four repeats, and work your way up to six or eight.

Tempo Runs

Tempo runs are also known as lactate threshold runs–this is the point at which your body is unable to recycle accumulated lactate in the blood. This is a pace that’s anywhere between ten and 30 seconds slower than a 5k or 10k pace.

The goal of tempo runs is to increase your anaerobic threshold, thus allowing your body to sustain an effort that was previously unsustainable. This training technique tends to benefit longer-distance runners more than sprinters.

Tempo runs should be part of a weekly running routine, and can vary depending on experience level and training needs. One way to incorporate this into training is to start by running 15 - 20 minutes at 75% of maximum heart rate, then build up to 30 - 45 minutes by adding about five minutes to these runs weekly.

Strength Training

While many runners are laser-focused on logging miles, time in the gym can lead to time off your mile splits.7

Two areas of strength training are often employed by runners: leg and core workouts. Weight training can both improve strength and lead to greater running economy (as it did for female runners in this study).8

Exercises like lunges and squats can strengthen those leg muscles used more frequently on runs. And for core workouts, even simple additions like planks and leg raises and weighted sit-ups can positively impact form and posture. Don’t discount yoga and stretching–on days where you’re looking for some active recovery, yoga is perfect for both developing strength in core muscle groups and stretching tight muscles.

Fix Your Form

Essential to running efficiently, improving running form and technique can lead to faster speed. The way you run affects the way force is applied to your muscles and joints. Correcting form can be help injury prevention, as improper execution can cause injury if you’re a beginner;9 if you aren’t running, you aren’t getting faster.

“People assume that running is running is running, but it's not true. Especially when we sit at our desks all day, or aren't used to it.” — Michael Brandt, HVMN Co-founder and COO

Good overall form can feel like a unicorn; it’s best broken down into a few manageable techniques to consider on each run.

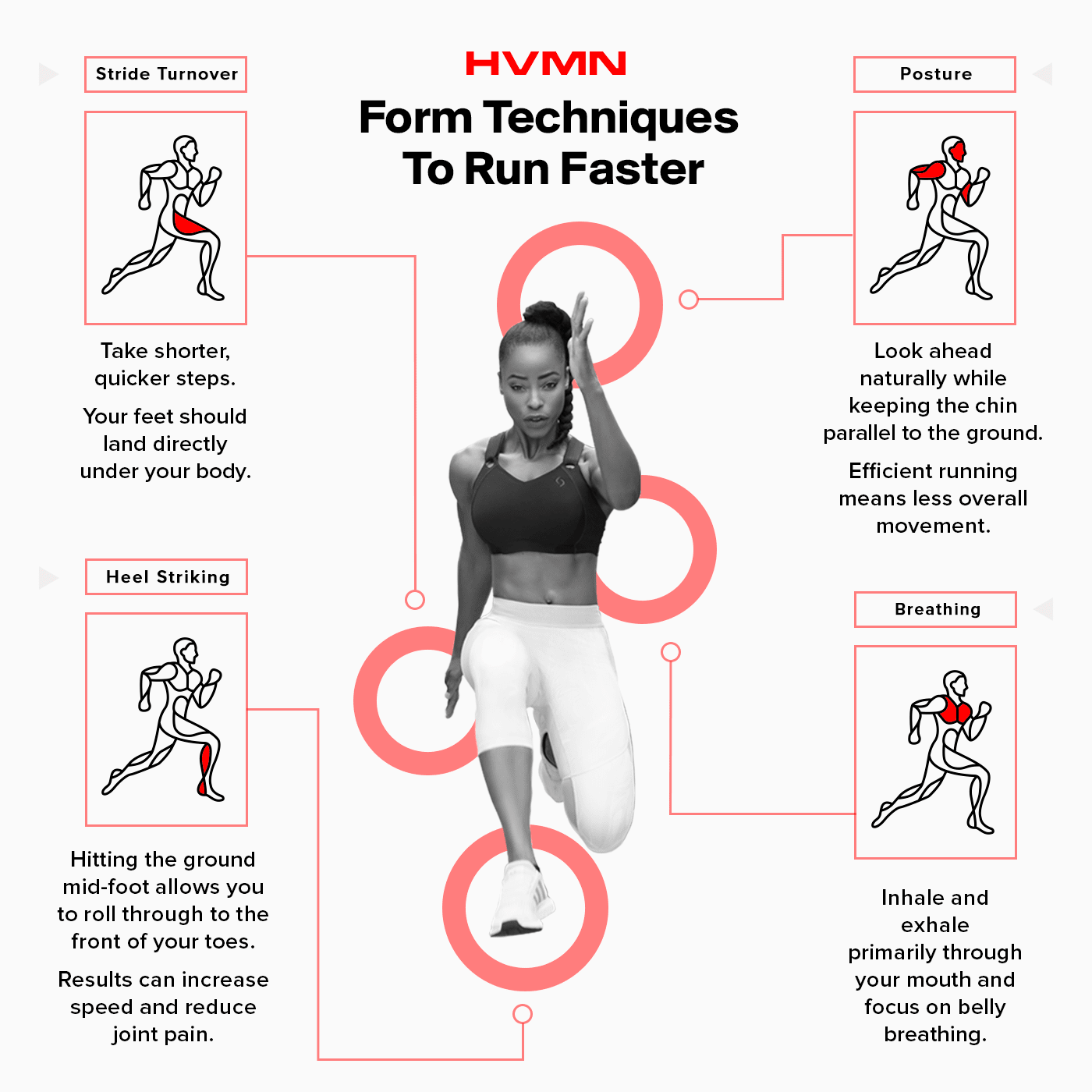

Stride Turnover

Changing stride turnover–how my steps taken during one minute of running–may have an impact on speed.10

The goal is to have a higher stride turnover, meaning to take shorter, quicker steps; these reduce the impact on your joints because you’ll hit the ground with less force. Longer strides have the opposite effect, and can create more impact because you’re in the air for longer. Sprinters will typically need to lift their knees higher to achieve maximum leg power, but distance runners won’t need as much lift.

Figuring out your stride turnover is easy. Just run for one minute at your 5k pace and count the number of times your right foot hits the ground. To improve stride turnover, jog for one minute to recover, trying to increase your stride count by one. Repeat this several times with the goal of increasing strides each time.

At the proper stride length, your feet should land directly under your body. And when your foot strikes the ground, your knee should be slightly flexed, bending naturally to the impact. Keep in mind that the middle of your foot should be making contact with the ground–not your heel.

Heel Striking

It’s a very common problem for runners.11 Landing on your heel can mean too long of a stride, which wastes energy and may cause running injuries (hello, shin splints).12 Avoid landing on toes too–this can also increase fatigue and wear out your calves.

You want to be a mid-foot striker. Hitting the ground mid-foot allows you to roll through to the front of your toes. Changing your footstrike takes practice, but the results can show up both in speed and in reduced joint pain. One study of runners from habitually barefoot populations showed an increase in speed when mid-foot or front-foot striking.13

Overstriding is usually the culprit–try increasing your number of strides. Your next run, focus on striking on the balls of your feet. Interestingly, that’s where most people strike when running barefoot; try running on grass (or another soft surface) without any shoes on, translating that muscle memory to other runs. Also, running drills can help. Skipping, high knees, side shuffling, butt kicks–with all these, it’s almost impossible to land on the heel.

One last thing. It may seem obvious, but keep those toes pointed in the direction you want to travel. As fatigue sets in, form gets wonky–you may find your toes are turning in or out, which can lead to joint pain.

Relax

It goes from top to bottom and will have an impact on running posture.

Relax your shoulders. Relax your arms. Relax your hands.

Posture

“Running tall” is a repeated mantra meant to encourage good running posture.

It starts with the head: look ahead naturally while keeping the chin parallel to the ground, and avoid looking down at the feet. This should improve posture in your neck, shoulders and back–which, remember, should be relaxed.

Avoid hiking up your shoulders, which can happen naturally with stress. Upon feeling your shoulders close your ears, try giving them a good shake to relax and keep them level.

Efficient running means less overall movement. Arms, at a 90-degree angle, should swing back and forth around the waist, powering the lower body. Think of yourself as two halves: left and right, and keep each arm on that side of the body. Tension in the upper body is controlled by the hands, so relaxed hands are also important. You may notice tension developing throughout the run as it gets more difficult–imagine you’re carrying an egg in each hand and watch that tension disappear.

The torso and back should be naturally straight, as this promotes optimal lung capacity and stride length. Slouching during a run? Try a deep, realigning breath and hold position.

Breathing

We’ve discussed VO2 max, and its impact on the body’s ability to use oxygen efficiently. Since oxygen is feeding those muscles, it’s important to understand how to take in the most air possible.

Inhale and exhale primarily through your mouth–it’s the most effective way to take in oxygen. Your nose can join the party too, but it can be difficult for some to breathe through both simultaneously. Practice makes perfect here; you can try it throughout the day to help get the body adapted to the technique.

And focus on belly breathing, with the force of the inhale extending to the diaphragm with the stomach expanding. These should be deep, slow, rhythmic breaths. Overall, you should see a decrease in cramps and an increased ability to pace yourself.

Sleep & Recovery

The importance of rest cannot be understated–but it’s often forgotten or unaccounted for in a training plan.

“Our culture has a ‘no pain, no gain’ mindset. But that’s not how the body works exactly. You need to recover properly.” — Sam Robinson

Sleep and recovery days are important to give tired muscles a chance to rebuild tissues that have been broken down during exercise.14 That breakdown is meant to cause muscles to adapt and become stronger, thus potentially leading to increased speed. Sleep is also part of this process. It’s important to encourage good sleep: set a sleep schedule and get some screenless time before bed, because screens can negatively impact rest.15 One study found that lack of sleep can lead to muscle degradation.16

Recovery runs are a must. These should be done at a slower, less-strenuous pace that allows the body to recycle lactate as its produced. This pace per mile should be about one minute or 1:30 more than your average pace.

Consuming Your Way to Speed

What you eat, and the supplements you take, can have an impact on how fast you run. A body operating on high-octane fuel will undoubtedly perform better than one with a less-optimized fuel source.

Diet

Diet can have a roundabout effect on speed through a few different avenues.

It directly impacts body composition, which affects speed. It can also determine the body’s fuel source, meaning that a diet low in carbohydrates can lead to fat-adaptation, allowing the body to tap into fat stores. If you aren’t a fat burner, carbs are essential to keep running pace, as glycogen depletion leads to bonking. And after a run, diet can help with recovery, enabling the body to train again faster.

VO2 max is a measure of one’s running fitness; it’s the maximum amount of oxygen that can be delivered to working muscle per unit of body mass. Those with higher VO2 maxes are better runners. And because body weight impacts VO2 max, the lighter the runner means a higher VO2 max which can mean a lighter runner is a better runner.

Many distance runners are employing the ketogenic diet for weight loss. The low-carb, high-fat diet can force a metabolic adaptation allowing the runner to burn fat as fuel (as opposed to carbs). And the restricting of carbohydrates often leads to better body composition.

Counting calories may help you lose weight. While the macronutrient composition of food can be more important than the amount of calories, counting calories while on keto might lead to greater results.

Supplements

We’ve covered supplements for runners extensively, providing you with a toolkit from training to race day to recovery. You’ll want to focus on those for race day, as they’re the supplements that can have a direct correlation to speed.

Many runners drink coffee and consume carbohydrates before a race, giving the body fuel sources to immediately tap into. Buffers are also useful, and may delay the onset of muscle pain associated with the building up lactic acid in the blood (but really it’s the proton associated with lactate)–check out sodium bicarbonate, Beta-alanine and HVMN Ketone.

HVMN Ketone

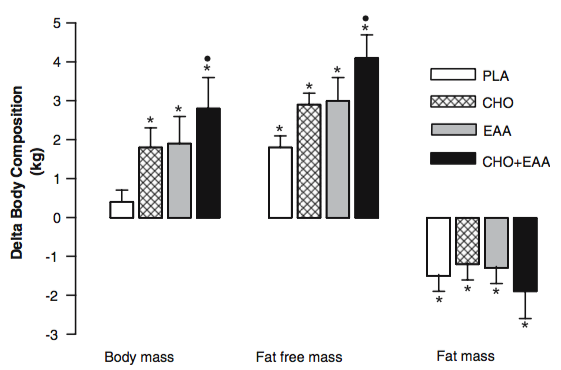

Ketones are a fundamentally different fuel source from carbohydrates and fats that cells normally use for energy.

Taken before or during exercise, D-BHB (the ketone body in HVMN Ketone) is 28% more efficient than carbohydrates alone, helping your body do more work with the same amount of oxygen.17 In one study, cyclists went ~2% further in a 30-minute time trial.18

When taken with carbs, the glycogen-sparing effect of HVMN Ketone helps many runners–the body will preferentially use the ketones as fuel first, saving glycogen for later in the race, when the need it most.

"By consuming exogenous ketones, athletes give themselves an additional source of fuel that they can burn first, thus preserving glycogen." — Allison Goldstein, Runner’s World

HVMN Athlete and professional cyclists, Vittoria Bussi, recently broke the world record for the women’s Hour: riders see how far they can cycle in a velodrome in one hour. Vittoria used HVMN Ketone before her attempt, citing its effectiveness later in the race.

Read more about Vittoria’s story here.

Running Fast: a Personal Pursuit

With countless ways to measure and track and compare and share statuses, it’s important to remember that on a run, it’s just you and the road. You should want to improve. You should want to get faster. You should expect to work to get there.

Running isn’t about taking shortcuts, if you want to get faster, you have to train. Aspire to some of the world’s best runners, and use that as motivation each time you lace up your shoes to run.

Want to get even faster?

We're currently exploring nutritional techniques to improve performance. Subscribe, and be first to know when our guides are published.

Scientific Citations

1.Brandon LJ. Physiological factors associated with middle distance running performance. Sports Med. 1995 Apr;19(4):268-77.

2.Hatzigeorgiadis A, Zourbanos N, Galanis E, Theodorakis Y. Self-Talk and Sports Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011 July; 6(4): 348-356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611413136

3.Haase L, May AC, Falahpour M, et al. A pilot study investigating changes in neural processing after mindfulness training in elite athletes. Front. Behav. Neurosci., 27 August 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00229

4.Dupont G, Akakpo, K, Berthoin, S. The Effect of In-Season, High-Intensity Interval Training in Soccer Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: 2004; 18(3): 584–589.

5.Franch J, Madsen K, Djurhuus MS, Pedersen PK. Improved running economy following intensified training correlates with reduced ventilatory demands. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise [01 Aug 1998, 30(8):1250-1256].

6.Ferley D, Hopper DT, Vukovich M. Incline Treadmill Interval Training: Short vs. Long Bouts and the Effects on Distance Running Performance. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2016 Aug; 37(12). DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-109539

7.Storen O, Helgerud J, Stoa EM, Hoff J. Maximal Strength Training Improves Running Economy in Distance Runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 1089–1094, 2008.

8.Johnston RE, Quinn TJ, Kertzer R, Vroman NB. Strength training in female distance runners: Impact on running economy. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 11(4):224-229. 1997

9.Kluitenberg B, van Middelkoop M, Diercks R, van der Worp H. What are the Differences in Injury Proportions Between Different Populations of Runners? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2015; 45(8): 1143–1161. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0331-x

10.Hogberg, P. Arbeitsphysiologie (1952) 14: 437. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00934423

11.Larson P, Higgins E, Kaminski J, et al. Foot strike patterns of recreational and sub-elite runners in a long-distance road race, Journal of Sports Sciences. 2011;29:15, 1665-1673, DOI: 10.1080/02640414.2011.610347

12.Daoud, AI, Geissler GJ, Wang F, Saretsky J, Daoud YA, Lieberman DE. Foot Strike and Injury Rates in Endurance Runners: A Retrospective Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 44, No. 7, pp. 1325–1334, 2012

13.Hatala KG, Dingwall HL, Wunderlich RE, Richmond BG (2013) Variation in Foot Strike Patterns during Running among Habitually Barefoot Populations. PLoS ONE 8(1): e52548. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052548

14.Parra J, Cadefau J A, Rodas G, Amigo N, Cusso R. The distribution of rest periods affects performance and adaptations of energy metabolism induced by high‐intensity training in human muscle. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 169: 157-165.

15.Exelmans L, Van den Bulck J .Bedtime mobile phone use and sleep in adults. Soc Sci Med. 2016 Jan;148:93-101.

16.Dattilo M, Antunes H K M, Medeiros A, Mônico Neto M, Souza H S, Tufika S, de Mello M T. Sleep and muscle recovery: Endocrinological and molecular basis for a new and promising hypothesis. Medical Hypotheses Volume 77, Issue 2, August 2011, Pages 220-222.

17.Sato, K., Kashiw.aya, Y., Keon, C.A., Tsuchiya, N., King, M.T., Radda, G.K., Chance, B., Clarke, K., and Veech, RL. (1995). Insulin, ketone bodies, and mitochondrial energy transduction. FASEB J. 9, 651-658.

18.Cox, P.J., Kirk, T., Ashmore, T., Willerton, K., Evans, R., Smith, A., Murray, Andrew J., Stubbs, B., West, J., McLure, Stewart W., et al. (2016). Nutritional Ketosis Alters Fuel Preference and Thereby Endurance Performance in Athletes. Cell Metabolism 24, 1-13.